| Intended | |

|---|---|

if (test 1) if (test 2) statement 1; else statement 2; |

|

If-statements are among the most simple and the most easily understood control statements. Their simplicity notwithstanding, if-statements are powerful and essential in contemporary programs written in various programming languages. If-statements follow one of three basic formats:

Each format is explored in detail below. The conditional expression driving each if-statement in the following code fragments is abbreviated simply as "Test" or "Test n." This convention is just a shorthand notation representing a logical Boolean-valued expression, which may be simple or arbitrarily complex. For example: counter < 10 or counter > 0 && counter < MAX

A simple if-statement executes a single statement, whether a block statement or not, depending on the test outcome. We generally base the tests on the values stored in one or more program variables. The results of the tests change as the values stored in the variables change during program execution, which means that the statements inside the if-statement execute sometimes but not other times. The following flow chart illustrates the behavior of a simple if-statement.

The code fragments below demonstrate the basic pattern of a simple if-statement. The definition of a statement given previously is applied recursively here. That is Statement 1 is a single statement, but so is if (Test) Statement 1 (the complete statement ends with a single semicolon). The second and third examples each form single if-statements; the braces form a block that the if treats like a single statement (note the absence of a semicolon following the closing brace). Finally, in the second example, the braces surrounding "Statement 1" are optional - some programmers always use braces, while others do not.

if (Test) Statement 1; |

if (Test) { Statement 1; } |

if (Test) { Statement 1; Statement 2; } |

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

int x = 10; if (x > 0) cout << "it is greater than\n"; |

int x = 10; if (x < 10) cout << "it is less than\n"; |

it is greater than

|

No output |

Whereas a simple if-statement chooses to execute a statement or not, an if-else statement chooses to execute one of two statements, either or both of which may be a block statement, as illustrated in the figure below.

else separates the statements. As before, braces are optional when a single statement appears in either the if or the else branch.

"Statement 1" always follows the keyword if, while "Statement 2" always follows the keyword else, as illustrated by the patterns below. A well-formed if-statement requires the if keyword, the parentheses, and a valid test, but the else and the associated statement are optional.

if (Test) Statement 1; else Statement 2; |

if (Test)

{

Statement 1;

.

.

.

Statement n;

}

else

{

Statement 1;

.

.

.

Statement m;

}

|

| (a) | (b) |

An if-else ladder does not introduce additional keywords or symbols. The statement forms each new ladder rung with an if-else statement nested inside the else part of the previous if-else statement. If-else ladders also represent an exception to the earlier rule of thumb to restrict nesting to no more than four or five levels; the nesting must be deep enough to accommodate every possible branch required by the problem logic.

The following code fragments demonstrate the basic if-else ladder patterns:

if (Test 1) Statement 1; else if (Test 2) Statement 2; else if (Test 3) Statement 3; else if (Test n) Statement n; |

if (Test 1)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement j;

}

else if (Test 2)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement k;

}

else if (Test 3)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement l;

}

else if (Test n)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement m;

}

else

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement n;

}

|

| (a) | |

if (Test 1) Statement 1; else if (Test 2) Statement 2; else if (Test 3) Statement 3; else if (Test n) Statement n; else Statement m; | |

| (b) | (c) |

if (Test 1)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement j;

}

else

if (Test 2)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement k;

}

else

if (Test 3)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement l;

}

else

if (Test n)

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement m;

}

else

{

Statement 1;

Statement 2;

. . . .

Statement n;

}

| if-else statement | if-else ladder |

|---|---|

int x = 5; double y = 3.14; if (x > y && x != 10) cout << "true\n"; else cout << "false\n"; |

int score = 87; if (score >= 95) cout << "Grade: A\n"; else if (score >= 90 && score < 95) cout << "Grade: A-\n"; else if (score >= 85 && score < 90) cout << "Grade: B+\n"; else if (score >= 80 && score < 85) cout << "Grade: B\n"; else if (score >= 75 && score < 80) cout << "Grade: B-\n"; else (score < 75) cout << "Grade: E\n"; |

true |

Grade: B+ |

else part of the previous statement. Both examples illustrate more complex conditional tests and the output from the code fragments.

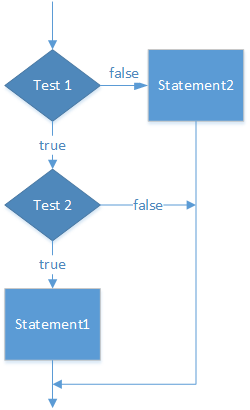

It's essential to remember that we use indentation in a C++ program to make the code's logic more apparent to people. Indentation is not part of the language's syntax and does not affect the meaning of the code in any way. (Alternatively, indentation is relevant in a Python program where indentation rather than braces indicate nesting.) The "dangling else problem" results from an over-dependence on indentation. Look very closely at the indentation in the first code fragment, which suggests what the programmer intended the code to do. The accompanying logic diagram also illustrates the programmer's intention.

| Intended | |

|---|---|

if (test 1) if (test 2) statement 1; else statement 2; |

|

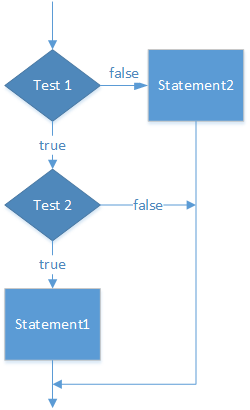

| Actual | |

|---|---|

if (test 1) if (test 2) statement 1; else statement 2; |

|

else lines up with the matching "if." Now, it's easier to see the code's true behavior, as illustrated in the logic diagram.

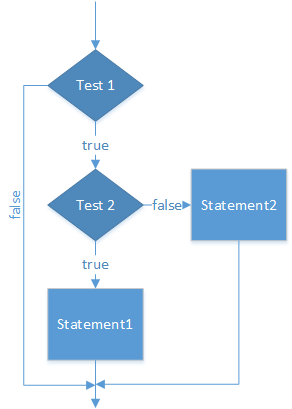

| Corrected Statement | |

|---|---|

if (test 1) { if (test 2) statement 1; } else statement 2; |

|

else clause always binds to the nearest if clause.

If you are interested in a more technical description of the problem and its history, you can read more in the Wikipedia article Dangling else.