|

const char* target = "HELLO WORLD"; const char* s1 = strchr(target, 'L'); const char* s2 = strrchr(target, 'L'); if (s1 != nullptr) cout << s1 << endl; if (s2 != nullptr) cout << s2 << endl;Output: LLO WORLD LD |

Searching in a target string to locate a specific character or substring is a task encountered in some text-processing programs. This section describes and demonstrates four C-string functions and two variants that provide various searching options.

|

const char* target = "HELLO WORLD"; const char* s1 = strchr(target, 'L'); const char* s2 = strrchr(target, 'L'); if (s1 != nullptr) cout << s1 << endl; if (s2 != nullptr) cout << s2 << endl;Output: LLO WORLD LD |

|

const char* target = "HELLO WORLD"; const char* s3 = strstr(target, "WORLD"); if (s3 != nullptr) cout << s3 << endl;Output: WORLD |

Parsing (also known as tokenizing) a string is a common data processing task. Parsing assumes that some groups of characters within a string, called tokens, have meaning in some context and that other characters, called delimiters, separate the groups. Programmers parse or tokenize a string by scanning it, looking for the delimiters, and separating the individual tokens. Programmers can use the C-string library function strtok (for string tokenizer) to help them complete simple parsing tasks.

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

It's necessary for the strtok function to "remember" the current parsing location between function calls. The typical implementation accomplishes this task with a static variable (see Figure 5), preventing the function from simultaneously processing multiple strings. The Microsoft and Linux versions add a third parameter, context. Think of this double pointer as a pointer to a C-string, making it an INOUT parameter. (See Figure 7 for examples, and Returning Non-Local Data for a discussion of a similar problem.) The target, delims, and returned value are identical to the "typical" function.

strtok scans the target from left-to-right. Whenever it finds a delimiter, it replaces it with a null-termination character and returns a pointer to the extracted token. It ignores multiple adjacent delimiters, and delimiters at the beginning or end of target. It returns nullptr after extracting all the tokens.strtok in two different ways. They begin parsing target with call (i) and continue parsing (extracting the remaining tokens) with call (ii) in a loop. The following code fragments demonstrate the basic logic:

token = strtok(target, delims);

while (token != nullptr)

{

// process token

token = strtok(nullptr, delims);

} |

token = strtok(target, delims);

do

{

// process token

token = strtok(nullptr, delims);

} while (token != nullptr); |

for (token = strtok(target, delims; token != nullpter; token = strtok(nullptr, delims))) // process token |

|

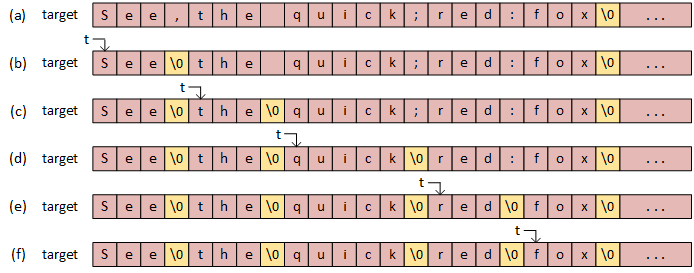

char target[100] = "See,the quick;red:fox"; const char* delims = " ,:;";The order of the delimiter characters is not significant. When the delimiters include a space, I put it at the beginning of the delimiter string, where I find it easier to see. The example shows how the parsed string, target, changes with each call.

strtok returns a pointer, represented by t, to each token.

char* t = strtok(target, delims);, replaces the comma with a null-termination character and returns a pointer to See.t = strtok(nullptr, delims);.

char* strtok(char* target, const char* delims)

{

static char* context = nullptr; // initialized once at program load

if (target != nullptr) // begin parsing a new string

context = target;

// parses string and sets context

return token;

}

static pointer variable to save the current parsing position between function calls. The code fragment illustrates one possible way to implement this behavior.

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

char target[100] = "See,the quick;red:fox";

const char* delims = " ,:;";

for (char* token = strtok(target, delims); token; token = strtok(nullptr, delims))

cout << token << endl;

//char* token = strtok(target, delims); // for while and do-while versions

/*while (token)

{

cout << token << endl;

token = strtok(nullptr, delims);

}*/

/*do

{

cout << token << endl;

token = strtok(nullptr, delims);

} while (token);*/

return 0;

}

The standard strtok function relies on a local static variable (a variable defined in the strtok function) to save the current parsing location within the target. So, if the program begins parsing a second string before finishing the first, the function loses the parse position in the first string. That is, programmers can't begin parsing string-A, switch to parsing string-B, then return to parsing string-A. The Microsoft and Linux versions eliminate this restriction by replacing the local static variable with the context parameter, whose corresponding argument is defined in the client's scope.

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

const char* delims = " :";

char target1[100] = "See the quick red fox";

char target2[100] = "jump:over:the:lazy:brown:dog";

char* context1 = nullptr;

char* context2 = nullptr;

char* token1 = strtok_s(target1, delims, &context1);

char* token2 = strtok_s(target2, delims, &context2);

while (token1 != nullptr || token2 != nullptr)

{

if (token1 != nullptr)

cout << token1 << endl;

token1 = strtok_s(nullptr, delims, &context1);

if (token2 != nullptr)

cout << token2 << endl;

token2 = strtok_s(nullptr, delims, &context2);

}

return 0;

}

|

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

const char* delims = " :";

char target1[100] = "See the quick red fox";

char target2[100] = "jump:over:the:lazy:brown:dog";

char* context1 = nullptr;

char* context2 = nullptr;

char* token1 = strtok_r(target1, delims, &context1);

char* token2 = strtok_r(target2, delims, &context2);

while (token1 != nullptr || token2 != nullptr)

{

if (token1 != nullptr)

cout << token1 << endl;

token1 = strtok_r(nullptr, delims, &context1);

if (token2 != nullptr)

cout << token2 << endl;

token2 = strtok_r(nullptr, delims, &context2);

}

return 0;

}

|

| Microsoft | Linux |

|---|

static variable with a third parameter. Figure 3 names the parameter context, but programmers are free to choose any appropriate name. context performs the same task as the local static variable by saving the current parsing location. However, defining context in the application program's scope allows the application to parse multiple strings simultaneously without conflict.

Aside from the slightly different function names, both programs are identical. context is a C-string - a character-pointer: char*. However, strtok_s and strtok_r modify it, so the program must pass it with an INOUT mechanism, and they use pass by pointer. So, the strtok_s and strtok_r prototypes presented in Figure 3 show the type as a pointer-to-a-pointer: char**, and the program finds the variable's address with the address-of operator (shown in red).