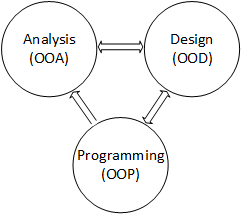

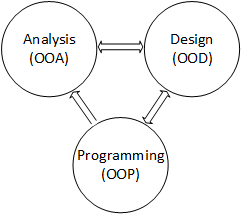

Class development spans three distinct phases of the software development process: analysis, design, and implementation. Initially, Analysts view a problem through an object-oriented lens, identify the objects they find, and abstract them into domain classes. They also identify the data the system maintains and the operations it performs, initially assigning the features to classes according to their "natural responsibilities." UML class diagrams are a convenient way to capture and organize these observations.

Developers refine the domain classes during the design phase. They discard extraneous classes and add implementation classes (classes that don't exist in the problem but are necessary for a program). They also discard, add, modify, and relocate features during the design phase.

In the final phase, programmers express the classes as working program components. One of the benefits of an object-oriented development lifecycle is that it maintains a consistent "vocabulary" of classes throughout the process. The domain classes identified during analysis and the implementation classes added during design are the same classes that appear in the final program.

Contemporary software development methodologies include these phases in extensive development processes. Some are suitable for rapidly designing software, while others are better suited for designing large systems that must function for many years. Although many methodologies are in use today, there isn't an algorithm for selecting classes, attributes, or operations. Consequently, developers generally apply the phases in cycles, initially focusing on small components (e.g., individual classes) and refining them until the component is functional. You will formally study some methodologies in subsequent courses. Here, we take a more informal approach focused on individual classes.

Another object-oriented approach to software development is to view a class from two different perspectives: the class developer or the class user. The developer focuses on organizing the class's data and implementing the service it supplies. Alternatively, the class user treats the class as a black box, focusing on how it can help solve a problem while ignoring its internal details. The distinction is greatest for general, reusable classes, where the developer imagines all the services the class should supply. The string class is a good example: developers can't foresee all the programs that will use it, but they can imagine the services it should supply. Conversely, programmers using the string class don't need to know how it works, only what it does.

The two-hat technique is a helpful way to differentiate between the two roles. Although it may be the same person or group creating and using a class, it's beneficial to adopt the appropriate perspective. You may switch between the developer and user roles quickly and frequently, but pausing briefly and intentionally shifting your perspective results in better code.

| Server / Supplier | Client |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

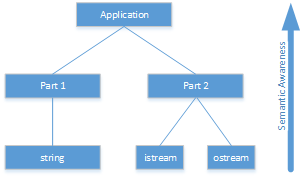

It is often insightful to treat classes as living entities that can do things. For example, imagine organizing the classes in an object-oriented program like a company's organizational chart. The director at the top knows the company's long-range goals but not how to design a program or an electric circuit. Mid-level managers know the details of a specific project but not the company strategy or detailed system design. Engineers know how to design software and circuits, but not how to run a company or manage a project. Similarly, the classes at the top know what the program does but not how it does it. Classes near the bottom of the hierarchy have detailed knowledge of solving a small part of the problem, but they don't know how their contributions work with the other classes in the program.

Software developers typically create classes near the top of the hierarchy to solve a specific problem, often using them in only one program. As such, developers specialize the top-level class features to meet the particular needs of that program. Classes become more general and reusable as you go down the hierarchy, with developers frequently using many general-purpose library classes at the bottom. These classes provide a broad set of general services focused on the class rather than a specific problem.

Choosing what operations to put in a class is similar to making a shopping list. Sometimes you make the list with a specific meal in mind, and other times with general "pantry" items you might need. The top classes are like the "specific meal" lists, and the bottom classes are like the "pantry items." The previous string example demonstrates a "pantry" list: its numerous operations might help some program.

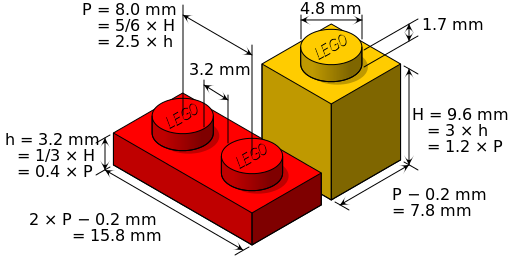

In general, an interface is a "place where two things come together and affect each other," a place where they "touch" and where they can interact. A class's interface is how a client connects to, interacts with, or uses an instance of the class. A class's interface includes all non-private features (i.e., attributes and operations) that are visible and accessible to other classes. C++ and Java have in common three keywords that control feature accessibility: public, protected, and private (Java also has a default accessibility that C++ does not). private is the only level of accessibility that completely excludes a feature from a class's interface, and public features are part of the class's public interface. Lego™ blocks are a second metaphor (besides the cookie-cutter mentioned previously) for objects. The objects fit together to form structures by matching posts of a precise size, orientation, and spacing on one Lego with compatible sockets or holes on a second Lego. The posts and holes are the Lego's interface.

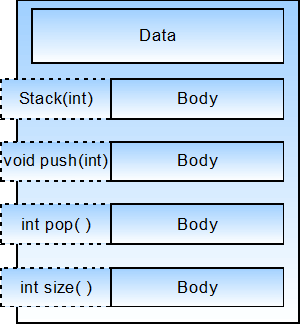

Similarly, a class's features form its interface; its public features that it exposes are its public interface. Typically, a class's public interface consists of its public member functions but can occasionally include public member variables as well. Figure 4 is an abstract representation of an object. Objects encapsulate or hide their data and their operation's algorithms (i.e., the bodies of the member functions) but expose the function's signatures (the function name, return type, and argument list). A client can use the object by just "knowing" the public interface - it does not need to know the private features or how the functions perform their tasks. The public interface effectively separates the how from the what.

"Lego dimensions" by Cmglee - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

As a general rule of thumb, programmers usually make attributes private and operations public, but the UML and C++ both support private operations and public attributes. Any non-private feature becomes part of the class's public interface. Making an operation private is appropriate whenever the class uses it internally, but it does not represent an external service. Typical examples include operations that represent code shared by two or more operations, or when a programmer decomposes large, complex operations into smaller, simpler sub-operations. These "helper" functions are appropriately private in a UML diagram and a corresponding program class (regardless of the implementing language).

Conversely, non-private data makes maintaining a stable public interface much more difficult. A stable public interface is one in which features (operations and attributes) are not removed or changed once they become available to client programs. Programmers may add new features to a public interface without adversely affecting its stability. However, once client code can use a public interface feature, that feature cannot be withdrawn or modified without potentially affecting existing client code. So, you should have a compelling reason to make an attribute non-private, and articulating your reason is a prerequisite for making that design decision.

Classes and objects help software engineers manage the complexity of increasingly large programs by providing concrete implementations of several abstract programming constructs.

void sort();. Later, when we have more time, we rewrite the function based on the quick-sort algorithm, but as long as the function signature, void sort();, does not change, the class's interface remains stable and any existing client code is not adversely affected.int counter;

Similarly, Person (which we will assume is the name of a class) can be used to specify the type of a variable:

Person manager;Computer scientists characterize ADTs by the operations they support (i.e., their public interface).